New questions arise about a peculiar 2,800-year-old burial on Crete

Over the past quarter century, excavations at the Iron Age necropolis of Orthi Petra at Eleutherna on Crete, under the direction of Greek archaeologist Nicholas Stampolidis, a professor at the University of Crete, have yielded fantastic finds. In the 1990s, for instance, the cremated remains of 141 aristocratic men—who likely fell in battle abroad and were honored with burials fit for Homeric war heroes—famously came to light. But the latest discoveries, a stone’s throw from the warriors’ collective tomb, have most captivated me because they radically alter our understanding of the role of women, once thought to be “inferior” to men, in the so-called “Dark Ages” of Greece. Successfully evading the archaeologists’ trowels until 2007, a dozen female individuals are now known to represent an incredibly wealthy and powerful female bloodline, the first and only-known discovery to date of its kind in Greece.

In July 2009, I visited the enchanting—arguably, “enchanted”—burial site, ensconced deep inside the foothills of Mt. Ida, the mythological birthplace of the omnipotent god Zeus. Silvery-green olive trees, bright patches of wild flowers, and fragrant herbs surround the 2,800-year-old cemetery. The burial ground itself teems with life: yellow butterflies gently hover above partially exposed human skeletons and cicadas chirp in stereo, from the depths of the graves and the shadows of the environs, at times so loudly it seems as though the dead are singing.

Tomb of the Priestesses, 2010 excavation of gold strips (Photo © Prof. N. Ch. Stampolidis)

When I visited, a “Dynasty of Priestesses,” four in total, had just came to light in an elaborate, “built” rock tomb, and I reported on the find for Archaeology magazine. Having “met” the ladies face to face—huddled atop each other in the center of the tomb—and having stood inside their final resting place, still brimming with earth-encrusted ceramic amphorae and smelling of freshly turned dirt, I feel a special connection to the story. These closely related women, ranging in age from early teens to late adulthood, were accompanied to the afterlife by incredible grave goods of gold, silver, bronze, and semiprecious stones imported from as far away as Egypt and the Near East, as well as ritual implements, such as a tiny bronze saw for making sacrifices and a pristine glass phiale, or vessel for pouring libations to the gods.

One of dozens of thin gold strips crafted in the "international" style found in the Tomb of the Priestesses in 2010 (Photo © Prof. N. Ch. Stampolidis)

The unprecedented find was noted as a “Top 10 Discovery of 2009” but it is even more incredible in the site’s larger context. Researchers soon understood that some eight female individuals buried nearby in three pithoi (large ceramic jars, a typical burial practice of the time)—excavated between 2007 and 2009—were related not only to each other, but also to the priestesses. (While the pithos burials were equally lavish, they did not contain ritual implements that would suggest these women, too, were priestesses.) The finds had begun to illuminate a significant, unbroken female bloodline, or matriline, which spanned from the late ninth through the early seventh century B.C.

A year later, in 2010, I couldn’t wait to hear about what had come out of the ground next. By September, newspaper headlines touted the discovery of a skeleton “covered in gold.” I had to learn more. So recently, I caught up with Professor Stampolidis and forensic anthropologist Anagnostis Agelarakis, a professor at Adelphi University, who both graciously shared the details with me, and kindly permitted me to relay them on my blog.

I would like to offer heartfelt thanks to Professors Stampolidis and Agelarakis for taking the time to discuss these extraordinary discoveries with me and congratulate the entire team on another tremendously successful excavation season!

Lekythion excavated in 2010 from the Tomb of the Priestesses (Photo © Prof. N. Ch. Stampolidis)

Orthi Petra, Eleutherna: 2010 Highlights

In 2010, the archaeologists continued to excavate the Tomb of the Priestesses, unearthing lids belonging to the amphoras (jars) discovered in 2009, Cypro-Phoenician and Phoenician glass perfume jars, faience Egyptianizing lekythoi (oil flasks), and a bronze phiale. According to Professor Stampolidis, the “most extraordinary” recent finds from the tomb were dozens of thin strips of gold—some measuring 15×4 and 16×4 centimeters—as well as gold jewelry reflecting an “international” style. The latter pieces were expertly crafted in the “cut-out” and repoussé techniques known from Syro-Palestine, Cyprus, Asia Minor, the Aegean islands, and other parts of Crete, and depict images such as heraldic goddesses.

New tomb found in summer 2010 behind a one-meter-think wall (foreground) and a large rectangular tombstone (Photo © Prof. N. Ch. Stampolidis)

Last summer, new excavations were also undertaken a few meters to the south of the Tomb of the Priestesses. “We were trying to clean up a peculiar wall, resembling an ancient retaining wall made of local limestone,” says Stampolidis. “We soon realized that in the middle of that wall, it looked as if there were a doorway, possibly leading to a tomb.” Team members cleared the area, but when they had already gone farther than the thickness of the wall, about a meter, they found only earth and rough stone—no traces of a tomb. But they didn’t give up. “It was due to our persistence and instinct that we dug a few feet farther toward the east,” notes Stampolidis. They suddenly saw that a huge, partially hewn tombstone, almost 1x1x0.20 meters, was covering the mouth of a nearly two-meter-tall pithos. “The whole construction was like a rock-cut cave within which the pithos was placed,” he adds. “But at a distance, it looked as if the ancient Eleuthernians wanted to create the impression of a large entrance to deter tomb robbers.”

Inside the intact pithos, says Stampolidis, “We came across an extraordinary situation: instead of digging in earth, we found ourselves digging in small gold sheets and strips mixed with some earth.” In total, the team found more than 3,100 pieces of “cut-out” gold in varying shapes—circles, squares, and rhombuses—along with the skeleton of a young woman.

A sampling of more than 3,100 pieces of gold found in the 2010 pithos burial (Photo © Prof. N. Ch. Stampolidis)

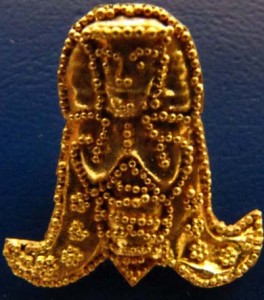

“The gold is extremely delicate,” says Stampolidis. “We soon realized that all this gold was probably knit on cloth, either a costume or even a burial shroud. We are now in the process of cleaning and straightening the pieces to find out their patterns and ‘logic,’” he says. Digging inside the pithos, team member Eva Mitakis also found other gold jewelry, including a stunning piece depicting a Bee Goddess and several in the shape of flowers, along with more than 300 beads of rock crystal, amber, cornelian, and amethyst. Also uncovered were small, glazed-faience perfume bottles. “But the most extraordinary of all,” insists Stampolidis, “were some tiny pieces of cloth, which show our interpretation about the costume or shroud is fully correct.” (The cloth is believed to be wool or linen but has yet to be analyzed.)

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery in the burial, very close to the young woman’s lower legs, was a mass of bones belonging to another human skeleton, a young man. Professor Agelarakis is currently undertaking careful research to properly assess his age, which will be a critical piece of information in the burial’s interpretation. According to Stampolidis, “If he was between 15 and 17 years old, an ephebe, or adolescent, there is no problem with interpreting his inhumation.” Young boys during this period were commonly buried either directly in a pithos or in the ground. However, generally, citizens of a certain (high) status that were between 18 and about 60 years old were always cremated. “So if he is 18 or even older, why he was not cremated?” asks Stampolidis. “Is it, let’s say, the first example of changing the burial custom from cremation to inhumation? Or does it have to do with other postmortem beliefs?” Analysis of the accompanying finds is also expected to provide important clues. Discovered with the male individual were pieces of an iron dagger, an iron brooch, and (possibly) a small gold plaque. “The amazing thing is that his corpse was like a pile of bones at the feet of the woman,” says Stampolidis, “not extended like her skeleton or all other skeletons in the necropolis.”

Gold Bee Goddess from the 2010 pithos burial (Photo © Prof. N. Ch. Stampolidis)

Agelarakis hopes soon to release further information about the young woman, including whether or not she is believed to be related to the women in Eleutherna’s matriline—and if the remains of any other individuals come to light with further forensic analysis. In the meantime, is there reason to suspect the female individual was an important “priestess” as well? “Yes there are reasons,” says Stampolidis. “If you think of the ‘Bee Goddess,’ the gold flowers, the jewelry on her body—but especially, the way the young man lay at her feet. A wealthy individual could have the same characteristics but how the young man is going to be interpreted?”

According to Stampolidis, the appearance of the whole of the find—the “false door” hiding the tomb’s entrance, the gold jewelry, the inhumation of the young man—is unique among the other tombs in the necropolis of Orthi Petra. “We need to continue studying the artifacts and the human remains over the next few months and put together the pieces of the puzzle,” says Stampolidis. “The whole story from first sight is peculiar. It needs an interpretation, or at least some plausible solution. Will we see changing customs or new beliefs—connected, for example, with Egypt and ideas of Orphic-Pythagorean beliefs, absorbed in a Cretan environment and with Cretan manners? Foreigners? A priestess and ‘consort’ from a kind of a hieros gamos [holy marriage] or…or…or…? We cannot say just yet!”

Hi I stumbled on your blog by mistake when i searched Msn for this subject, I need to point out your webpage is quite very helpful I also really like the design, it is great!

And just how is it possible to tell that the women were priestesses and not simply members of the elite?