An exhibition of southern Chinese bronzes deepens our understanding of the ancient world

To the untrained eye, an exhibition comprised solely of ancient Chinese bronzes, no matter how rare and beautiful, may be difficult to appreciate. So I was fortunate to be guided through “Along the Yangzi River: Regional Culture of the Bronze Age from Hunan” at New York’s China Institute Gallery by its director Willow Weilan Hai Chang.

On loan mostly from the Hunan Provincial Museum, the 70 bronze works on view—bells, vessels, and weapons—date to the Shang (ca. 1600–1100 B.C.) and Zhou (ca. 1100–256 B.C.) dynasties and are especially significant because of where they were found. China’s Bronze Age culture was long understood to have flourished mainly in the center of the country, along the Yellow River. The works in the show, however, were all unearthed in the south, along the Yangzi. “People always thought the southern part of China was kind of like a remote place,” Willow explains. But a flurry of construction and infrastructure projects after the founding of New China in 1949 sparked a proliferation of archaeological digs throughout the country. “No one could have imagined such an ‘eccentric’ Bronze Age culture existed there.”

Nao (large bell) with animal design, Western Zhou Dynasty (Photo courtesy of China Institute Gallery)

Two striking nao (bells), illustrate that the south also had its own distinct style. “This type of large bell is not seen in the north in this period,” she says. Placed on a stand and rung with a mallet from the outside, these sizable objects weigh 176 and 220 pounds, respectively (other examples, not on view, weigh up to 450 pounds). Archaeologists find nao buried alone, directly in the ground, either alongside the Yangzi River or a couple hundred feet from the tops of mountains or hills. “Only the shamans knew where the nao were buried,” Willow explains. “On special occasions, they would return to the spot, take them out of the ground, use them in a ceremony, and then bury them again afterward.”

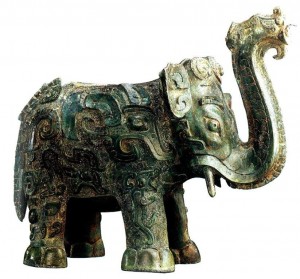

Each nao’s surface teems with animal motifs, which are characteristic of southern bronzes at this time. The overall appearance gives the impression of a fantastic beast—with bulging eyes and long, flat nose. Closer inspection reveals ready-to-pounce tigers and stylized elephants, both of which roamed the undulating Chinese landscape at the time. “Elephants show up often in southern bronzes,” she points out. During the Bronze Age, the massive creatures were trained to fight in wars and to plow farmers’ fields. “According to our ancient records, eventually there were so many that in the Western Zhou Dynasty [1100–771 B.C.], the Duke of Zhou once had to lead an army to shoo them away!”

Zun in the shape of an elephant, Shang Dynasty (Photo courtesy of China Institute Gallery)

A sophisticated, hollow bronze elephant—a ritual vessel for pouring liquids such as a fragrant, herbed wine—is also a highlight of the show. Fine bronze vessels such as this example are generally excavated from the tombs of noblemen, and indicate the deceased’s high rank. While it was likely stored in a family temple and used throughout the individual’s lifetime, it was also ultimately meant to accompany him to the afterlife upon his death. “This one, the Hunan Provincial Museum people call it like a ‘zoo,’” Willow tells me as she leans in for a closer look. Indeed, the piece is crawling with tigers, snakes, and bovine horns, even stylized elephant faces. “On the back of his big, fat ear there are two birds,” she adds with amusement.

Perhaps the most intriguing object in the show is a rectangular vessel with four legs (the style is known as a ding), which may have contained offerings used in important religious ceremonies. On each side is a round face in relief, with well-defined eyebrows, high cheekbones, and fleshy, unsmiling lips. “I was knocked out by this ding,” Willow admits. “In China, we learn about it in our textbooks. This is the only one in the entire world that has human faces on it.”

Rectangular ding with human-face design, Shang Dynasty (Photo courtesy of China Institute Gallery)

The rare ding was accidentally discovered in 1959 by a peasant who promptly dismantled it and sent the metal to his local recycling station, dutifully following Mao Zedong’s vision at the time for China’s steel production to “catch up with England, surpass America.” Fortunately, a representative from the local museum got wind of the unusual piece and eventually tracked down all of its parts (the legs had been sent to another recycling station). “Now it’s complete, but you can find some of the modern joints,” Willow says. “Also, the legs are not perfectly even.”

Some scholars have suggested that the faces represent a shaman. Others argue that they depict a female tribal leader. “No one really knows,” says Willow. “This could be an important figure or maybe even a god,” she says, pointing out that each ear is flanked by a simplified snake and dragon. Inclusion of these elements may signify the individual’s power over the animals. Inside the vessel are two character inscriptions that may provide clues as to its purpose. One looks like a human being standing with open legs and outstretched hands. “That means ‘large’ in Chinese,” she explains. The other one looks like a stalk of young rice. “These two words could be joined together to create a word meaning ‘year.’ But it could also be translated as ‘big harvest.’”

Ax heads found inside the pou at left (Photo courtesy of China Institute Gallery)

Pou with animal-face design, Shang Dynasty (Photo courtesy of China Institute Gallery)

While many bronze vessels contained food, wine, or offerings, three unusual ones in the show were likely buried alone as caches in pits. They are displayed with the precious artifacts retrieved from their bellies: 320 pieces of jade jewelry, more than 1,172 jade beads, and 224 pocket-sized ax blades, respectively, a selection of which is on view in the exhibition.

One of my favorite, more modest vessels in the show is a gourd-shaped hu (ewer) with a sculptural dragon handle. “We have a special gourd-like worship in the southern part of China,” Willow explains. “It’s related with our ancestors who were saved in a gourd when we had a big flood. A brother and a sister hid inside it. Afterward, they kind of made all the human beings. In the West, you have the ‘Noah’s Ark’ and ‘Adam and Eve’ stories. In the southern part of China, we have the story about this gourd.” Gourds were also used as containers for wine, and later for medicine. In bands encircling the vessel’s body and neck are spirals, which have been interpreted as a “cloud-and-thunder” pattern, another typical southern motif. “In ancient times, every pattern, every thing on a vessel had its meaning. It wasn’t just for beauty.”

Gourd-shaped hu with a dragon handle, Western Zhou Dynasty (Photo courtesy of China Institute Gallery)

Through Willow, I have come to better understand not only China’s rich history, proud culture, and artistic traditions, but also the strength, generous nature, and gentle spirit of its people. I first met her in 2007, when I covered the gallery’s “Buddhist Sculpture” exhibition and we instantly connected over our shared passion for archaeology. She was among the first generation of students to return to university after the Cultural Revolution—the brightest of the bright—and one of a handful of brave young women who, though discouraged by her professors, insisted on excavating right alongside her male counterparts. Through an interview I later conducted with her, I came to admire her unwavering determination to produce the best-quality shows possible for the gallery as well as her insatiable curiosity for learning about each new subject she tackles—“I’m a Curious George,” she told me. “I always like to find out why, why, why!” Ever since, I’ve been bowled over by her expert knowledge of (and discerning eye for) a staggering array of Chinese art, from Neolithic jade earbobs to imperial calligraphy to contemporary painting.

“The bronzes in ‘Along the Yangzi River’ are not only objects,” she insists, “they’re kind of like ‘living fossils’ that show the ancient world to us. I hope the exhibition makes visitors want to know more about China—not only from an artistic point of view, but also to know its climate and geography at that time; to understand people’s lifestyles and beliefs. I hope, through these bronzes, people will develop a deeper understanding.”

“Along the Yangzi River: Regional Culture of the Bronze Age from Hunan” is on view at the China Institute Gallery (125 East 65th Street, New York, NY) through June 12, 2011.