Mummies and artifacts from the Silk Road show how connected we once were

Beginning in the late second century B.C. the Silk Road, a vast web of trade routes spanning from the Mediterranean basin to India to China, connected the world’s great civilizations. For some 1,500 years, this ancient network facilitated the exchange not only of goods—ceramics, glass, furs, ivory, jade, lacquer, metals, silk, and spices—but also of ideas, customs, and religious beliefs. More than 100 objects excavated from numerous gravesites at the crossroads of these famous arteries in Central Asia’s Tarim Basin desert are on view in the exhibition “Secrets of the Silk Road” at Philadelphia’s Penn Museum. Dating to both before and after the Silk Road’s formation, the wide variety of artifacts, such as a wooden statuette of a veiled equestrienne and a plush felt hat, along with two famous mummies and the burial garments of a third, help to tell the still-unraveling story of the people who lived there.

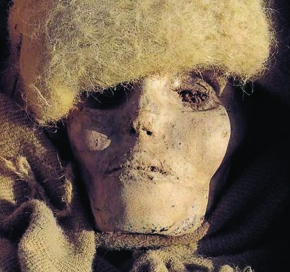

Infant mummy, ca. 8th c. B.C. (Photo © Wang Da-Gang)

Victor Mair, curatorial consultant and professor of Chinese Language and Literature at the University of Pennsylvania, makes no “secret” of his favorite object in the exhibition: a bronze figurine of a kneeling warrior (below) that dates to about 500 B.C. “He’s just mystifying, you know?” he says, noting its kilt, bare chest, round eyes, long nose—and Phrygian helmet. “The first time I saw him 25 years ago, I said, ‘This guy is Greek! What’s he doing out here?’ At first, I thought it was a fluke. But then they found another one almost like it 20 years later.”

Bronze kneeling warrior, ca. 500 B.C. (Photo © Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Museum)

As he leans in for a closer look at his old friend, it’s exciting to be there when he notices something new. “Actually, you know what? I used to think that’s a clavicle, his bone structure,” he says, pointing out the area just below the figure’s neck. “But now I’m thinking it’s a torque! So, okay, that’s even more interesting because he has a torque!” (There’s a similar-looking torque in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Greek and Roman collection. Personally, I did a double take on a female figurine [in the rotating gallery below] dating to about 1800 B.C. that looks like it could be Cycladic.)

One of my favorite objects in the exhibition is a sliver of a spring roll (also shown in the gallery below) that looks more like a stale leftover languishing in my fridge than a bite-size snack someone enjoyed 1,400 years ago. But the most breathtaking sights in the exhibition are an eighth-century B.C. infant mummy wrapped in a cuddly blanket (above, center); the trappings of “Yingpan Man” who stood at six feet, six inches tall (below, left); and “The Beauty of Xiaohe,” an exceptionally well-preserved female mummy dating to between 1800 and 1500 B.C. (below, right). Mair understands why people have been drawn to her since her 2003 excavation—even this great scholar seems to have a bit of a crush. “She’s got this serene attractiveness. People try to imagine what she would have been like when she was alive,” he tells me.

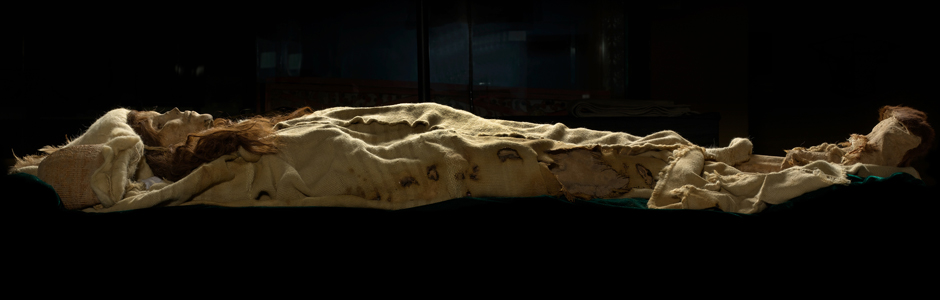

"The Beauty of Xiaohe" with her hat tipped to the side (Photo © Wang Da-Gang)

“It’s like she just went to sleep and she never woke up. She would have been dreaming for 3,800 years! What was she dreaming about?” I, too, want to know more about this woman Mair has dubbed the “Marlene Dietrich of the Desert”—because her hat was tipped to the side when she was unearthed—and it’s hard to leave the gallery where she lies in a Plexiglas coffin.

“I think when people look at her, first of all, they’re saying, ‘How can she be so well preserved?’ ” says Mair. “Number two, they’re saying, ‘Man, she’s beautiful!’ ” Indeed, wavy, flax-colored hair frames her face; long eyelashes, a ski-slope nose, and Mona Lisa smile make her simultaneously aloof and approachable (her hair is visible in the rotating gallery below). Her lovely Eurasian features have been a point of controversy that some have argued nearly got her pulled from the Penn Museum’s exhibition by the Chinese officials who lent them (see coverage by The New York Times). Even now, she is “napping” in Philadelphia for only three weeks.

She was a natural flax and a natural eternal beauty. Nearly 40 mummies from the same site as well as hundreds of others from the region are exceptionally well preserved—but no embalming materials were used. Three factors helped to preserve the Tarim Basin desert mummies as well as the textiles and organic remains: the cold, the dryness, and the salt in the soil. “The mummies that are well preserved usually died in the winter when it’s very, very cold and dry all the time,” explains Mair. “Before putrefaction can take place, the body dies. So they’re kind of like freeze-dried.”

"Yingpan Man," complete trappings (no mummy), 3rd-4th c. A.D. (Photo © Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology)

The harsh climate also played a factor in the excavation of the site nearly four millennia later. After Xiaohe was rediscovered around 2000, archaeologists were originally going to excavate the 23-foot-high burial mound over the course of 10 years. “But you can only work in there for a few months of the year because it’s too hot, too cold,” says Mair. “And as soon as the archaeologists would go away, then the looters would come back.” So instead, they decided to excavate quickly, taking down the whole mound in just three years, between 2002 and 2005. “They took out all the important artifacts, and then they built it up again—they put the sand back,” says Mair. “It was a very good excavation.”

Ongoing digs in the region are sure to provide even more clues about the people of the Tarim Basin desert. But the archaeologists have their work cut out for them. “There are huge cemeteries out there,” says Mair. “There’s one at Sampul that stretches on for 10, 15 kilometers [about six to nine miles], it’s enormous!” While settlements have not yet been excavated, I was surprised to learn that—judging just from their burials—these people are believed to have been quite economically level. “There was not much luxury,” says Mair. “I think it was subsistence living, agro-pastoralist. So you didn’t have an accumulation of wealth that was conspicuous for a particular burial. I mean, everybody tried to make themselves look nice and they had the basic, minimal, goods, like a basket.” I noticed that the Beauty is displayed with one by her head and asked if anything was found inside. “Grain!” says Mair. “Wheat or barley. And wheat is definitely from the West. The sheep and goats they had, too, are from the West. So they, themselves, came from somewhere, and brought this mode of living and their livestock with them. It’s so bizarre to find livestock out in the desert!”

Sorry, Facebook. I’d rather spend an afternoon wandering around this exhibition, marveling at how connected we once were before social media.

“Secrets of the Silk Road” is on view at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The artifacts and mummies will be displayed through Tuesday, March 15. From March 17 through March 28, the exhibition will continue with all of the artifacts but without the two mummies.

Thank you for your detailed observations and good quotations, for assembling so much valuable information, and for providing so many interesting links to follow and pertinent, clear photographs to view.