This spring’s ISAW exhibition looks at a distinct African civilization on its own terms

Miniature dagger, Kerma, 1700–1550 B.C.

Ancient Nubia has long been overshadowed by pharaonic Egypt, yet an increasingly clear picture of the mysterious land is finally starting to come to light. Among the most intriguing revelations have been that in certain periods Nubia was much more powerful than previously thought and that it had a rich and unique cultural heritage. Located in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan, Nubia is the focus of an exhibition at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) in New York titled “Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa.” The show features 120 artifacts spanning 2,500 years, beginning with the civilization’s rise in the late fourth millennium B.C.

“I felt that looking at Nubia was important,” says Jennifer Chi, associate director for exhibitions and public programs at ISAW. “It’s an area that I think is misunderstood.” Unlike Nubia, Egypt was a literate civilization, she points out, and surviving texts paint an unflattering picture its traditional enemy. “There’s a very biased viewpoint from the Egyptian side of Nubians being these uncultivated villagers.” The artifacts in the exhibition, however, tell a different story.

Pitcher in the form of a hippopotamus, Kerma, 1700–1550 B.C.

On view are the types of objects one might expect from a land that was also a trade partner of Egypt, including rigid shawabtis, necklaces with beads of carnelian and faience, even milky alabaster canopic jars. But then there are the marvelous surprises: a warrior’s ceremonial dagger with a delicate ivory handle (pictured above); a cattle skull painted with a still-vivid checkerboard pattern, mounted like a trophy in its display case; and a pair of three-inch-tall ivory pendants in the shape of flies, a Nubian symbol of military power for men and, possibly, fertility for women.

Other highlights include signature Nubian pottery, which beginning from about 3000 B.C. was extremely sophisticated—thin, refined, and elegant, even though it was all handmade. “I was trained in classical archaeology,” says Chi. “I never really realized that Nubian culture extended so far back and I didn’t realize the sophistication of the pottery technology from a very early period. It really speaks of specialization of craftsmanship and therefore having at least a settled village life from a very early period forward. That’s just fascinating to me.”

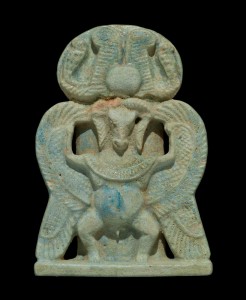

Winged ram-headed scarab amulet, faience, El-Kurru, 750–720 B.C.

In later periods, Nubia and Egypt shared, to an extent, a similar material culture. Nubians imported faience, for instance, which is strongly identified with ancient Egypt. By about 2000 B.C., there is evidence for large faience workshops in Nubia, in important urban centers such as Kerma. However, it seems that the adversaries didn’t have much else in common.

Nubia was made up of a loose federation of groups or tribes without a distinct leader like the Egyptian pharaoh. And whereas the Egyptians had clearly defined funerary practices for the burial of their royalty and elite in pyramidal structures, the Nubians instead had elaborate burial mounds surrounded by mud-brick walls, human sacrificial victims, and thousands of cattle skulls.

Egypt conquered Nubia around 1550 B.C., and there is evidence that Nubians served in the Egyptian army. However, Nubia later regained strength and emerged to overtake Egypt—ruling as its 25th Dynasty from about 750 to 650 B.C. “Nubia has a voice,” says Chi, “and it has a distinguished archaeological record that can really speak of its individual place in the history of ancient Africa.”

“Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa” in on view at ISAW through June 12, 2011. See an interview with guest curator Geoff Emberling, who has directed excavations in Sudan, in Through Nubian Eyes, Part II.