Kitschy carpets from Afghanistan unravel the mystery of a transforming rug market

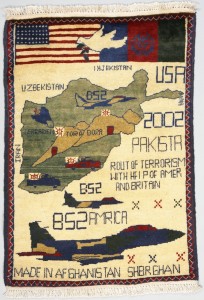

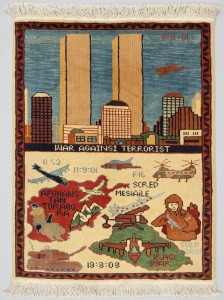

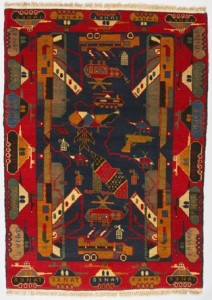

I’m a peace-loving person. So what drew me to the Penn Museum’s exhibition “Battleground: War Rugs from Afghanistan” wasn’t so much the sight of handwoven carpets loaded with bombs, helicopters, grenades, and tanks, but the opportunity to learn more about the people who made them, why they chose to depict such unusual imagery, and how these unique pieces wound up here.

I’m a peace-loving person. So what drew me to the Penn Museum’s exhibition “Battleground: War Rugs from Afghanistan” wasn’t so much the sight of handwoven carpets loaded with bombs, helicopters, grenades, and tanks, but the opportunity to learn more about the people who made them, why they chose to depict such unusual imagery, and how these unique pieces wound up here.

“The trouble with these carpets, generally, is that they’re all made since the country began to fall apart in 1979,” says Brian Spooner, curator of the Penn Museum’s Near Eastern section who specializes in Afghanistan and Oriental rugs. “Since then, it’s not been safe for people like me to go there and actually find out how things are done.” Spooner, an ethnographer and anthropologist, has worked in Afghanistan since the 1960s. “I spent a decade sitting on carpets,” he says, “and going with visitors to carpet stores and getting annoyed by what dealers told them about the carpets. They just made things up on the spot.”

So Spooner decided to undertake a study of Oriental carpets in the summer of 1972, visiting places where they were being made in northern Afghanistan. The following year, he invited a family of Turkmen carpet-weavers—a husband and wife, and their four-year-old daughter—to Philadelphia to create a carpet in the Penn Museum’s rotunda. “They wanted to do one with a portrait of President Nixon on it,” he says with amusement. “We politely declined.” Eventually, they reached a compromise: a small carpet featuring the museum’s logo.

So Spooner decided to undertake a study of Oriental carpets in the summer of 1972, visiting places where they were being made in northern Afghanistan. The following year, he invited a family of Turkmen carpet-weavers—a husband and wife, and their four-year-old daughter—to Philadelphia to create a carpet in the Penn Museum’s rotunda. “They wanted to do one with a portrait of President Nixon on it,” he says with amusement. “We politely declined.” Eventually, they reached a compromise: a small carpet featuring the museum’s logo.

The idea of producing a carpet for a specific clientele is relatively new, Spooner points out. Carpets have been woven in Afghanistan for at least 2,500 years, during which time they brimmed with sophisticated floral and geometric motifs. These images endured because historically carpet-weavers in Afghanistan were geographically isolated. “They’re cut off from the rest of the Islamic world and the rest of the world in general,” he explains. “And so the idea of weaving something that would be of interest to a larger public outside their own community didn’t occur to them until the beginnings of globalized processes in the 20th century.”

In recent decades, carpet-weavers and dealers began catering to Soviet soldiers and American GIs who were buying the rugs as souvenirs in the war-torn country. Some later sold their purchases into the international market. “The carpets you see here were all bought on eBay,” he adds, and then donated to the Textile Museum of Canada in Toronto where the exhibition originated.

In recent decades, carpet-weavers and dealers began catering to Soviet soldiers and American GIs who were buying the rugs as souvenirs in the war-torn country. Some later sold their purchases into the international market. “The carpets you see here were all bought on eBay,” he adds, and then donated to the Textile Museum of Canada in Toronto where the exhibition originated.

Spooner draws on his vast knowledge of Oriental carpets in general to illuminate the works on view in the show. The finest rugs are produced by children (child labor) on vertical looms in urban workshops, he explains, which are run by the royal palace or the power center. “What you’re looking at here come from a rural tradition that has grown out of nomadic tribes in Central Asia, woven by women and young girls on horizontal looms…The typical situation would be one in which the women do the work and the men tell them what to do. And then the men, of course, strike up relations with the dealers to get things sold. Then the men, very often, will give the women templates. They’re also copying from each other as well, I’m sure.”

But how do people feel about creating these new motifs, I wonder aloud. “This is the big question,” says Spooner. “This is the sort of thing that obviously you can only find out by going and talking to people.”

But how do people feel about creating these new motifs, I wonder aloud. “This is the big question,” says Spooner. “This is the sort of thing that obviously you can only find out by going and talking to people.”

Is it possible that the weavers are somehow rebelling against the war through these images? “I personally think that it’s a typical Western reaction to think that it must be ‘protest art.’ I think it’s ‘tourist art,’ ” says Spooner. “Imagine what it’s like: the fabric of your society has been totally torn apart. Much of your family has been broken up because they’ve had to flee as refugees. And you’ve got to make a living. What can you do? You can’t plow your fields—but you can weave. But you want to weave something you can sell immediately. And you see these foreigners here with money. What do they want? They’re fighting, they’ve got all these tanks and so on. Maybe they would like that. But they can’t talk to them to find out what they would like.”

As I wander the one-room gallery space—its walls painted desert tan punctuated with silent videos of U.S. troops projected high above the rugs—I’m overwhelmed by the violent imagery, occasionally interrupted by the juxtaposition of a pink-winged butterfly with a “butterfly land mine” or a string of upside-down hearts on the body of an AK-47. I ask Spooner what the public reaction to the works has been so far. “People don’t quite know what to do with them,” he says, making me feel a bit better. “But the fact is that this is a phenomenon that has transformed the Oriental rug market.”

As I wander the one-room gallery space—its walls painted desert tan punctuated with silent videos of U.S. troops projected high above the rugs—I’m overwhelmed by the violent imagery, occasionally interrupted by the juxtaposition of a pink-winged butterfly with a “butterfly land mine” or a string of upside-down hearts on the body of an AK-47. I ask Spooner what the public reaction to the works has been so far. “People don’t quite know what to do with them,” he says, making me feel a bit better. “But the fact is that this is a phenomenon that has transformed the Oriental rug market.”

“Battleground: War Rugs from Afghanistan” is on view at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology through July 31, 2011.